Life & Age of Man. Stages of Man’s Life from the Cradle to the Grave.

Lauren B. Hewes, Vice President for Collections and Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Graphic Arts, American Antiquarian Society

Examined only digital image.

Currier, Nathaniel, 1813-1888, artist.

Life & Age of Man. Stages of Man’s Life from the Cradle to the Grave.

New York, ca. 1847.

Hand-colored lithograph.

*GC – Allegories [P.2004.14.1]

Nathaniel Currier apprenticed as a printer in a lithography shop when he was 15, less than a decade after the 1819 invention of the lithographic process. By age 23 he had opened his own printing enterprise in New York. Eventually he would partner with James M. Ives (1824-1895) to create one of the nation’s best-known firms, Currier & Ives, publishing tens of thousands of affordable lithographs for nationwide consumption. But in the early 1840s, Currier was still on his own, trying to grow his profits by producing lithographs for the resale market. He advertised bulk sales to peddlers and travelling agents of 200 prints, including religious and moral subjects.[1] This allegorical scene illustrating the stages of a man’s life could have been among them.

As he was establishing his business, Currier printed reliable moneymakers, including portraits of American presidents, images of battles and marine disasters, and moral prints such as the Life & Age of Man. Like many publishers, Currier frequently copied designs by other artists to keep his stock fresh without having to shoulder the risk of creating a unique (and possibly unpopular) design – a common practice among printers that he would have observed during his apprenticeship.

Prints depicting the phases of human life have a long visual history starting in Renaissance Germany, and the tradition came to America with European immigrants.[2] “Stages of life” broadsides made in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts in the 1820s and 1830s borrowed elements from European versions such as the assignment of animals – a bull for the 30s and a cat for the 80s – and the inclusion of lines of poetry (fig. 1). These appear again on Currier’s 1840s lithograph, although he updated the costumes and offered his print with eye-catching hand-coloring.

It worked. Versions of Life & Age of Man appear in the firm’s catalogs for decades along with a companion piece Life & Age of Woman, and similar titles like The Seven Stages of Matrimony and the Drunkard’s Progress: From the First Glass to the Grave (fig. 2).[3] This staying power, while indicative of continued demand for “stages of life” prints by consumers, can also be viewed as representative of Nathaniel Currier’s understanding of his market – his model of selling cheap popular prints for the masses remained successful for over fifty years.

Keywords:

Allegory / Allegories

Nathaniel Currier

Stages of Life

Illustrations

Fig. 1. The Life and Age of Man. Carlisle, Pennsylvania: Moser & Peters, 1826. American Antiquarian Society.

Fig. 2. The Drunkard’s Progress: From the First Glass to the Grave. New York: Nathaniel Currier, 1846. Hand-colored lithograph. Gift of Charles Henry Taylor. American Antiquarian Society.

[1] New York Journal of Commerce (April 29, 1842): 4. His stock consisted of “about 200 designs among which are a great number of National, Temperance, Moral and Religious subjects.” The number in the lower margin of this print indicates that Life & Age of Man was assigned stock number #87.

[2] See Thomas R. Cole, The Journey of Life: A Cultural History of Aging in America (Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992). Also Julie Melby, “Resist the Devil and He Will Fly Far From You.” Princeton University Library, Graphic Arts Blog, April 2011.

[3] Currier & Ives: A Catalogue Raisonné (Detroit: Gale Research, 1983): 401-2.

Clayton Lewis, Curator of Graphic Materials, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan

Examined only digital image.

Title: The Life and Age of Man. Stages of Man’s Life From the Cradle to the Grave.

Format: Visual Material.

Main Author: Currier, Nathaniel, 1813-1888, artist.

Published/created: New York : N. Currier’s Lith., circa 1848

Contributors: N. Currier (Firm) publisher

Language: English

Copy-Specific Note: [Acquisition info]

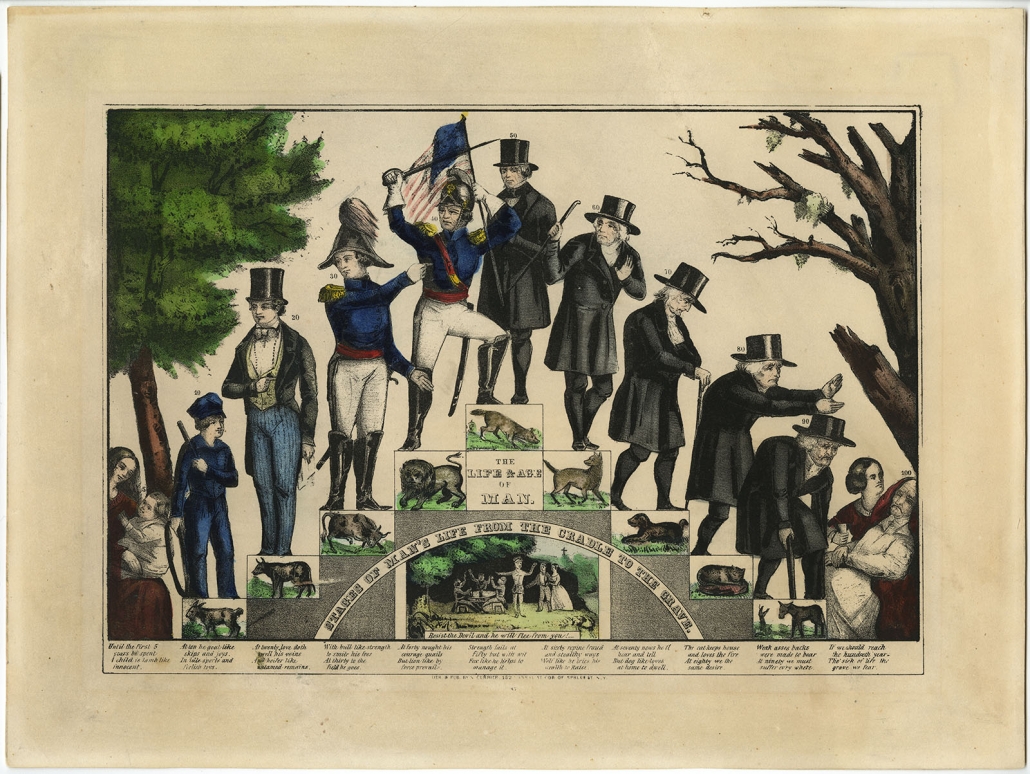

Note: Depiction of men at various life stages, from infancy to death. Includes 11 images of men ascending and then descending a set of steps with corresponding scenes of their lives, each accompanied with a verse connecting the human to an animal. The verses read:

(5) “Until the first 5 years be spent A child is lamb like innocent.”

(10) “At ten he goat like skips and joys In idle sports and foolish toys.”

(20) “At twenty Love doth swell his veins And heifer like untamed remains.”

(30) “With bull like strength to smite his foes At thirty to the field he goes.”

(40) “At forty naught his courage quails But lion like by force prevails.”

(50) “Strength fails at fifty but with wit Fox like he helps to manage it.”

(60) “At sixty repine fraud and stealthy ways Wolf like he tries his wealth to raise.”

(70) “At seventy news he it hear and tell But dog like loves at home to dwell.”

(80) “The cat keeps house and loves the fire At eighty we the same desire.”

(90) “Weak asses backs were made to bear At ninety we must suffer evry where.”

(100) “If we should reach the hundreth year Tho’ sick of like the grave we fear.”

Note: Vignette beneath the arched title reads: “Resist the Devil and he will flee from you!”

Note: Preceded by similar editions by Thompson and Alden, ca. 1835-1840, James Baillie, ca.1848, and the Kellogg Brothers ca.1848. Variant editions followed include Currier & Ives circa 1870s. Also multiple companion pieces, Life and Age of Women.

Note: Thomas R. Cole, The Journey of Life: a Cultural History of Aging in America (Cambridge [England]; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992)

Physical Description: 1 print : lithograph, hand-colored ; image 19 x 26 cm, on sheet 25 x 32 cm.

Subjects:

Men — Caucasian — 1840-1850.

Life cycle — 1840-1850.

Aging — 1840-1850.

Clothing & dress — 1840-1850.

Lithographs — Hand-colored — 1840-1850.

Allegorical prints — 1840-1850.

Conduct of life — 1840-1850.

This is a lithograph print in black ink with hand coloring, typical of inexpensive American 19th-century commercial lithographs. It depicts an allegory of a man’s life in eleven ascending and descending stages, progressing from left to right, from infancy to death at age 100. Each stage has a corresponding verse that compares aspects of life at that stage to the characteristics of a particular animal. The clothing and material clues of each stage vary to indicate growth, status, career, health, and decline. The military figure carrying a United States flag at stage five steps with one foot to the apex shared with a civilian figure at stage six. The stages are framed by two trees, the one on the left green and flourishing, the tree on the right leafless and dead. Centered below an arched title banner is a square vignette of a man being pulled away by a woman from a drinking scene. This image is subtitled “Resist the devil and he will flee from you!–”

Where Samuel Broadbent’s portrait daguerreotype of the unidentified African American woman interrupts normative stratified society, Nathanael Currier’s lithograph The Life &Age of Man reinforces it. Where a daguerreotype portrait is a singular unique image for a private audience, a commercial lithograph like this example was mass-produced and distributed nationally. While race is central in the photo as a presence, it is central to the print as an absence.

Inexpensive and available, Currier’s lithographs were a constant presence in many domestic parlors, public coffee shops, taverns, hotels. They were collected, shared, discussed, and laughed at during social gatherings. The influence of Currier, and his later partnership with James Merritt Ives, was enormous in determining and codifying mainstream Protestant white American behavior and expectations. The popularity of Currier & Ives illustrations of middle-class American cultural values extended into the 19th and 20th centuries. When we think of American nostalgia, many of us envision a Currier & Ives print.

Women are barely present in this sequence — a young mother leans into the picture on the left and an elder daughter presumably comforts the dying centenarian on the right. Our time traveler is dapper and smartly dressed as a young man, in military uniform twice as an enlistee and as a high ranking officer, proudly waving a sword and United States flag. At the pinnacle of “50” he becomes a civilian, conservatively dressed, and from that point on he descends, increasingly stoop shouldered and gray.

In addition to this mildly amusing sequence there is a warning, centered at the bottom: Resist the Devil and he will flee from you! This is coupled with a vignette of a woman pulling a man from the lure of intemperance.

What does this lithograph say about life’s expectations? Certainly there is a presumption of binary gender identity, and that the path for men is completely different than that for women. The women’s path is in fact a different lithograph. On the path for men, women are present and necessary at the beginning, but otherwise unseen until the end. Patriotism and valor are expected, and past fifty, one is no longer an active participant in society. Financial means are presumed, apparently earned when young (age twenty holding some papers), or in military service before middle-age. Temperance and piousness will lead to security, although the drinkers do appear to be having all the fun. Barely present are travels and adventure outside of the military, creative production, and meaningful social interactions. Religion is featured, not as a path to enlightenment but as an avoidance of everlasting hell.

This print corresponds to and reinforces established “normal” society as white, Christian, Protestant, patriotic, sober, conforming, and predestined. Hanging in a simple frame in the parlors of thousands of American middle-class homes, this lithograph establishes normative behavior to be followed, or to be rebelled against.

Keywords:

Establishment

Expectation

Constraints of society

Manhood

Growth

Images of disempowerment

Tanya Sheehan, William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Art, Colby College

Examined only digital image.

Currier, Nathaniel, 1813-1888, artist.

Life & Age of Man. Stages of Man’s Life from the Cradle to the Grave.

New York: N. Currier, [ca. 1847].

Hand-colored lithograph.

*GC – Allegories [P.2004.14.1]

Keywords: Christian values; bourgeois whiteness; patriarchy; masculinity; femininity

Description:

Tracing a single man’s life from boyhood to old age, this popular print maps onto American manhood values associated with white bourgeois Christianity in the antebellum period. Arranged in a pyramidal structure and proceeding from left to right are depictions of the white male protagonist at eleven different stages of his life. The narrative begins with a wide-eyed five-year-old child and ends with a feeble man of one hundred years. Nine stages exist between them, each separated by a decade. Below the man at every stage are four lines of verse that invoke an animal; the beast itself appears above the text, conveying something about his character at a particular age.

Although the print focuses on an ideal man and his maturation, women play an important but limited role within the narrative: that of doting caretaker. A mother cradles her loving child at five years old; a daughter (or nurse) tends to the elderly man as he nears death. These images of womanhood echo artistic depictions of the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ—specifically, the Renaissance tradition of the Madonna and child and that of the pietà, in which Mary supports the body of the dead Christ. Another female presence is suggested in the print, though not seen, in the representation of the man as bourgeois gentleman-suiter at age twenty. Sporting a dapper top hat, waistcoat, and cravat, he stands poised to offer his handkerchief to a young lady, as love “swell[s] his veins.” That the artist chose to compare the man’s twenty-year-old romantic self to an “untamed” heifer, or a young female cow who has not yet had a calf, would surely have struck 19th-century viewers as funny. This clearly feminized masculinity starkly contrasts the images of virile manhood that follow at ages thirty and forty, in which he dons the uniform of an army officer and evokes the strong bull and courageous lion. Women are therefore given considerable power at one moment in the young man’s life, when he is weakened by female charms. The same idea is repeated in a companion print produced by Currier & Ives, Life and Age of Woman: Stages of Woman from the Cradle to the Grave, which describes the female protagonist at age twenty as “a full blown flower.” The “heart of manhood feels her power,” but soon she becomes a subordinate figure who “clings” to her husband, mothers his children, and cares for their home. Feminizing the male protagonist of Life and Age of Man as a heifer may have troubled Victorian audiences, since subsequent versions of the print changed the twenty-year-old man’s animal comparison to an eagle, noted for its strength and dominance as a hunter.

A final female figure appears as part of a finely dressed bourgeois couple within the vignette at the print’s bottom center. Walking arm in arm, the couple encounters a semi-clothed man who beckons them toward a table at which well-dressed men drink and gesture wildly. Quoted from James 4:7, the scene’s caption—“Resist the devil, and he will flee from you”—frames the semi-clothed figure as tempting the goodly couple to a life of sin. Their Christian duty, the Bible instructs, is to submit themselves to God. Familiar with artistic representations of the Garden of Eden, period viewers might have expected to see the woman pictured as the man’s corruptor. But in this encounter with the devil, it is the woman—and the bourgeois domestic life she embodies—who calls the man back from his vices. Note the conspicuous placement of a Christian cross looming over the trees above the wifely figure, and just under the portrayal of the aging man in his most unvirtuous state: like a wolf, at age sixty he resorts to fraud and stealth to increase his wealth. It is through women’s lives of care and virtue, the print argues, that men like the protagonist may find their way into the kingdom of heaven.

Joy O. Ude, Art teacher, Howry STEAM Academy

Examined only digital image.

Currier, Nathaniel, 1813-1888, artist.

Life & Age of Man. Stages of Man’s Life from the Cradle to the Grave. New York: N. Currier, [ca. 1847].

Hand-colored lithograph.

*GC – Allegories [P.2004.14.1]

Keywords/Subject headings: Stages; Lithograph; Representation.

Stages of a Man’s Life. As I closely scrutinize the images and text of this lithograph, I wonder: what warrants the detailed documentation of a man’s life? What’s the criteria? Are the stages represented in this lithograph aspirational, a template for success? Are they considered typical of the time period?

I review the lithograph a second, third, and fourth time, and it becomes more apparent that it’s like an infographic for the life of a particular type of man. A man born into a life free from life’s worries. A man to whom all the privileges and opportunities of the world are assured. A man for whom everything falls perfectly into place.

Stages of a Man’s Life, only if one is afforded every basic need and resource, allowing him to maintain that “lamblike innocence.” (5 years)

Stages of a Man’s Life, only if the Devil does indeed flee when you resist. But what if society has labeled you the Devil? (all stages)

Stages of a Man’s Life, only if one makes it beyond the stages of bull or dog. (30 and 70 years)

Where is the lithograph, the poster, the visual for the life of a man whose stages are suddenly cut short? Where are the images for the man whose stages do not progress so logically and lineally? Where is the illustration for the man whose stages are pre-determined, shaped by society without his knowledge or consent?

It’s evident, that as with much of the history of this country, you won’t see such descriptive recognition of the life of the Indigenous man. No such representation for the man that was once counted as 3/5ths of a man. No lithograph for the man that suffered through internment generations later.

Stages of a Man’s Life. A life likely portrayed by those with the power and freedom to enjoy such a simple, successful version of a life.