North Side of Chestnut St., Extending from Sixth to Seventh St., 1851.

Lauren B. Hewes, Vice President for Collections and Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Graphic Arts, American Antiquarian Society

Examined only digital image.

B.R (Benjamin Ridgway) Evans, 1834-1891.

North Side of Chestnut St., Extending from Sixth to Seventh St., 1851.

Philadelphia, ca. 1880.

Watercolor.

Evans watercolors [P.2298.44]

Gift of Girard Bank and the Friends of the Library Company, 1975.

At first glance, this watercolor depicting a block of busy Chestnut Street in Philadelphia seems to be a faithful depiction of one of the city’s important commercial thoroughfares. Much of the visual information, along with the inscribed title, support the easily-made assumption that the drawing dates from 1851. The buildings are scaled properly for mid-century and the second Chestnut Street Theater, a famous landmark with its carvings of Tragedy and Comedy by William Rush, stands near the corner. In actuality, however, the watercolor was made in the 1880s by artist/architect B. R. Evans.[1] In the 1880s, this section of Chestnut Street was lined with modern gas lamps and telegraph poles, had trolley tracks running down the middle, and the theater (which burned in 1856) had been rebuilt seven blocks away. What gives?

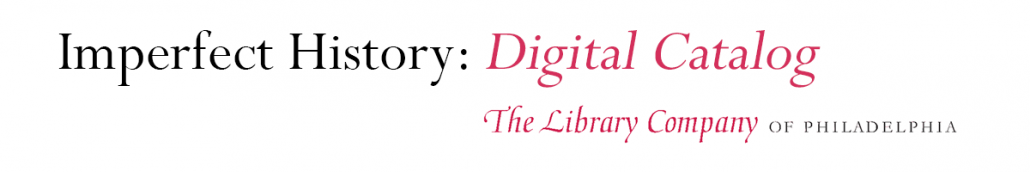

In the 1880s, Evans was commissioned by wealthy city resident and antiquarian Ferdinand J. Dreer (1812-1902) to create a series of scenes of “old” Philadelphia, many based on printed sources and photographs.[2] For this image, Evans likely relied on Rae’s Philadelphia Pictorial Directory & Panoramic Advertiser, published in 1851.[3] The illustrations in Rae’s practical publication are more plan-like than pictorial, carefully delineating shops to allow readers to easily locate specific businesses (fig. 1). Evans reduced the commercial clutter by editing out smaller establishments and modified Rae’s diagram-like design, depicting the street at a more visually pleasing angle. A large expanse of sky allows light to flood down onto the view uninterrupted, and the scene is animated with figures moving up and down clean, wide sidewalks.

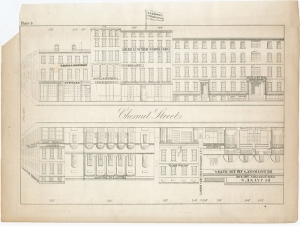

The watercolor is a revisionist view intended to please a patron. Evans left out any evidence of the city’s free black and immigrant populations – the majority of his figures appear to be white and middle class. The usual jumble of posters and sign boards that typically would appear around the theater have been omitted. Photographs from the 1850s and 1860s show a narrower, darker Chestnut Street edged by awnings and covered in advertising signage (fig. 2). While Evans may have used Rae’s directory as a way to see thirty years back in time, his decisions to omit populations and declutter the scene meant that he did not accurately represent 1851 Philadelphia.

None of this likely mattered to the elderly Dreer, who during his lifetime had witnessed the effects of multiple fires in the city and saw the population explode after the Civil War as waves of immigrants from central and southern Europe arrived. When he commissioned the drawings, Dreer was undoubtably aware of the changes caused by repeated cycles of rebuilding and expansion as the city added new transport hubs, trolleys, sewers, gas lights, and telegraph lines, changing forever the Philadelphia of his memory.[4] At times of transformation, some cling to the past, look back and revise what they remember, elevate some aspects while negating or ignoring others. The series of views by Evans, including the north side of Chestnut Street, are evidence of this practice.

Keywords:

Antiquarianism

Chestnut Street

Cityscape

Illustrations

Fig. 1 Julio H. Rae, Rae’s Philadelphia Pictorial Directory & Panoramic Advertiser (Philadelphia, 1851), plate 9. Library Company of Philadelphia.

Fig. 2. Album compiled by Joseph Y. Jeanes, Chestnut St. Looking East from about Half Way Above 9th St., ca. 1863. Unprocessed in PR 13 CN 2014:109 [P&P]. Library of Congress.

[1] Evans lists himself as a “practical architect” formerly with Hoxie & Starkwether in the Sunday Dispatch, October 14, 1855, p. 2. His obituary in the Philadelphia Inquirer (July 16, 1891): 6, does not mention an occupation.

[2] Dreer was frequently called an antiquarian in the press, see “Murdoch and the Prentices,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, April 13, 1883, p. 8. Library Company of Philadelphia holds more than 150 of Evans’ designs, which were purchased as a group from the sale of Dreer’s collection in 1913 before coming to LCP in 1975. See Library Company of Philadelphia Annual Report, 1975, p. 6-11. See also Stan V. Henkels at Samuel T. Freeman & Co., Oil Portraits & Engravings. The Collection of the Late Ferdinand J. Dreer, Esq. of Philadelphia. Catalog 1087 (June 6, 1913): lots 170-175.

[3] Julio H. Rae, Rae’s Philadelphia Pictorial Directory & Panoramic Advertiser (Philadelphia, 1851): plates 9 and 10.

[4] Quarter of a Millennium: The Library Company of Philadelphia, 1731-1981 (Philadelphia: The Library Company, 1982): 330. The authors describe the Evans watercolors as depicting structures that were “progress-threatened.” Federal census figures show the city’s population increasing from 121,376 in 1850 to 847,170 by 1880.

Clayton Lewis, Curator of Graphic Materials, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan

Examined only digital image.

Title: North side of Chestnut Street extending from Sixth Street to Seventh St. 1851.

Format: Visual material

Main Author: Evans, Benjamin Ridgway (artist)

Contributor: Dreer, Ferdinand J. (Ferdinand Julius), 1812-1902

Published/Created: Philadelphia.: circa 1880s

Language: English

Physical Description: 1 watercolor on paper, 25 x 32 cm

Copy-Specific Note: [Acquisition info]

Subjects:

Watercolors

Philadelphia (Pa.)

Urban streetscapes.

Chestnut street — Philadelphia (Pa.)

This item is a horizontal format panorama watercolor depicting the architecture, storefronts, signs, and people along a 19th-century commercial city block in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as it appeared in 1851. The vantage point is slightly above eye-level, from the corner of Seventh Street on the south side of Chestnut Street, looking across to the north side. Pedestrians comprised of colorfully dressed men and women populate the brick sidewalks while horse-drawn vehicles, apparently a private coach, public stage, omnibus, and commercial delivery wagon occupy the street under a cloudless sky. It is signed “B. Evans” in the lower right corner and dated lower left “1851.” The painted image sits within a ruled border, the title is hand printed across the bottom margin in capital letters.

The watercolor illustration “North Side of Chestnut Street Extending from Sixth Street to Seventh St.” by Benjamin Ridgway Evans documents a street in the city of Philadelphia as it once was. This image also records what wasn’t.

This streetscape gives us a panorama that simulates a stroll down the sidewalk of a thriving commercial district while gazing at the opposite storefronts. It represents a nostalgic look at Philadelphia’s urban scene of the 1850s. The emphasis is on the businesses that occupied the storefronts, many of which have been identified with rendered signs. The pedestrian and vehicle traffic are to some degree engaged with the commerce represented. The atmosphere is one of mercantile activity, prosperity, and opportunity. The streetscape is neat and orderly, tidy and clean.

This watercolor is one of a group of 151 commissioned in the late 19th century by Philadelphia jeweler Ferdinand Julius Dreer to document the passing of old Philadelphia as it was being erased by a building boom.

Evans brought a professional architect’s skill in perspective drawing and projections of constructions not yet in existence. And like many architects, the human figures are indicators of scale, anticipated activity, an idealized and positive presence however generic. In this case, the architect is projecting back in time to show a streetscape as it had previously existed.

With any work of visual art, we expect that some aspects of a given scene will be emphasized and others left out. The intent of Evans’s views seem to have been to represent the everyday history as experienced by many Philadelphians, in a commercial setting. This image does not chronicle the most famous historic sites of Philadelphia such as Independence Hall, just down Chestnut Street, however, John Haviland’s innovative Philadelphia Arcade, basically a 19th–century shopping mall of ninety retail stores, is clearly marked.

The rapid growth and redevelopment of the city demolished and removed much of Philadelphia’s earlier architecture of the sort that appears here. It is also a document of erasure in another sense. In spite of the detail and accuracy for the storefronts and businesses, and the emphasis on everyday life rather than major historic sites, Evans has omitted much of the human street life of the city and street activity that we know to have been present from other sources.

The first of the great visual chroniclers of urban Philadelphia, William Birch, published engraved views of what was at the time, the most important city in the United States at the start of the 19th century. Birch’s views are notable for the matter of fact inclusion of a population that cut across several classes of society, including street vendors, enslaved African Americans, and visiting Native American delegations. Birch’s Philadelphia shows a street parade of urban sights, sounds and smells. Although Evans’s view of Chestnut Street is also full of people, coaches, and omnibuses, the human presence appears filtered to the class of commerce and means. Is this an accurate representation of the street in the 1850s? Without further research into Philadelphia street society, I am speculating, but compared to Birch’s Philadelphia, Evans’s seems sanitized of the grit and sweat that paralleled and supported the commerce and trade.

What Evans does give us delineates an indistinct society (and architecture) that is clean, orderly, Anglo-European-American, and uniformly dressed. Opportunity, virtue, righteous honesty, conformity, and social stability are emphasized. The comfortably occupied street comes with orderly behavior, minimal interactions. In the Evans’ view, the only breaks from serenity are a newsboy who tails a well-dressed couple, hawking a paper; a man in stride appearing to be hurrying for reasons unknown; and another striding figure chases an omnibus.

Evans’s style of representation owes much to the enormously popular illustrated county atlases and local histories that celebrated middle-America in the 19th century. Like these, he presents an idealized urban America, designed to flatter established White society, an America that never really was.

So what does a historian do with source material like Evans’ views that represents the past but with obvious omissions? I suggest starting with the recognition that all historical sources, including visual materials, represent an opinion. From there, consider the appropriateness of the question being asked of the work. If one is seeking the exact and complete appearance of Chestnut Street, one may do better with photographs or written accounts. However, if one is looking to document how nostalgia can reshape historical memory, then Evans’s watercolor views are right on target.

Keywords:

Urban life

Streetscapes

Hotels

Stores

Commerce

Commercial architecture

Omnibuses

Nostalgia

Tanya Sheehan, William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Art, Colby College

Examined only digital image.

Evans, B. R. (Benjamin Ridgway), 1834-1891.

North side of Chestnut St., extending from Sixth to Seventh St., 1851.

Philadelphia, ca. 1880.

Watercolor.

Evans watercolors [P.2298.44]

Keywords: bourgeois marketplace; white middle class; commercial life in Philadelphia; fashions; patent medicine

Description:

Painted around 1880, this watercolor depicting a bustling Chestnut Street bears a striking resemblance to the streetscape prints that appeared in the 1851 edition of Julio H. Rae’s Philadelphia Pictorial Directory and Panoramic Advertiser. The businesses that bought their way into Rae’s popular directory sought to attract white middle-class customers to their doors, promising that the products and services offered would support their racial and class identities.

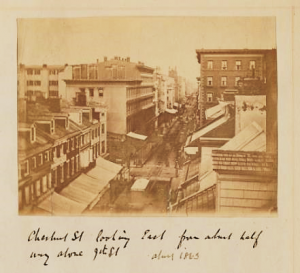

On either end of this single city block, we see shops that offered well-to-do customers therapeutic treatments for a variety of ills, including a druggist (A. S. Smith) and the storefront of a patent medicine maker (J. H. Schenck). Schenck provided consultations and examinations at his Chestnut Street office to anyone experiencing symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis, then known as consumption. Schenck’s Pulmonic Syrup promised to cure this disease, which in the mid-19th century was believed to affect those stereotyped as having sensitive dispositions, like the two white bourgeois women approaching Schenck’s shop door in the watercolor. Another famous patent medicine maker (David Jayne) owned the Arcade Building at the center of the block, which housed Dr. Davidson’s Arcade Baths. The cholera epidemic of 1849 led to the construction of bathhouses in large cities like Philadelphia, where gentlemen sought to rid themselves of dirt and its close associations with poverty and disease.

Elsewhere on the block are establishments where men and women could literally fashion themselves as ladies and gentlemen. To the left of the Arcade, for example, is the shopfront of a tailor (E. G. Dorsey), while farther down the street we see L. Benkert’s Boot Store and the publisher of the popular Philadelphia Fashions, which circulated the latest bourgeois clothing styles. Many of the figures in the watercolor look as if they walked out of a fashion plate, with men sporting trendy dark suits, top hats, and canes, and women wearing brightly colored dresses or skirts, shawls, and elegant headgear. These figures appear upright as they stand in conversation with one another, slowly promenade along the street, or gracefully mount the stairs of the Chestnut Street Theatre. This posture contrasts with those adopted by laborers in the scene, like the carriage drivers and newsboys, who lean or lunge in motion. Together the would-be customers and the people who serve them generate a bustling scene of activity, yet the street remains ordered and impossibly clean — even with all of those horses!

By the time Philadelphia jewelry manufacturer and antiquarian Ferdinand J. Dreer commissioned this watercolor reproduction of one of Rae’s streetscapes, three decades after its initial printing, this scene and the world around it had changed considerably. Some of the grand buildings in Rae’s original 1851 print had been destroyed, including the Chestnut Street Theatre (burned in 1856) and the Arcade (demolished by 1860). Many other businesses had closed or changed hands. The United States had also been through a bloody civil war and a failed period of Reconstruction. By attempting to recover the social order expressed in Rae’s vision of Chestnut Street, Dreer was perhaps assuaging the anxiety he and other privileged white Americans felt about the changes taking place across the country. His nostalgia for a genteel Old Philadelphia was, however, a fantasy in which commercial success and individual prosperity were afforded to a small slice of the population, to the exclusion of all others.

Joy O. Ude, Art teacher, Howry STEAM Academy

Examined only digital image.

Evans, B. R. (Benjamin Ridgway), 1834-1891.

North side of Chestnut St., extending from Sixth to Seventh St., 1851.

Philadelphia, ca. 1880.

Watercolor.

Evans watercolors [P.2298.44]

Keywords/Subject headings: Schenck’s; Landmark; Research

A watercolor, like a photograph, perfectly captures a moment in time. A precise historical image for a section of a bustling city. The same path where seventy-five years later the Continental Congress would walk to sign the Declaration of Independence. Today, the site of a police station, Italian consulate, and a Wawa.

I live for details, obvious and hidden — for the moments after the initial assessment of an object, which lead to a headlong deep dive into research. This watercolor does not disappoint.

The 1850s version of a shopping district: Along a commercial city block, I see sidewalks full of strolling citizens and streets busy with the traffic of carriages and horses. On shared wall buildings, I spot signs for a druggist, a tailor, two hotels, a bathhouse, and Schenck’s. Schenck’s is my Easter egg and the rabbit hole into which I descend.

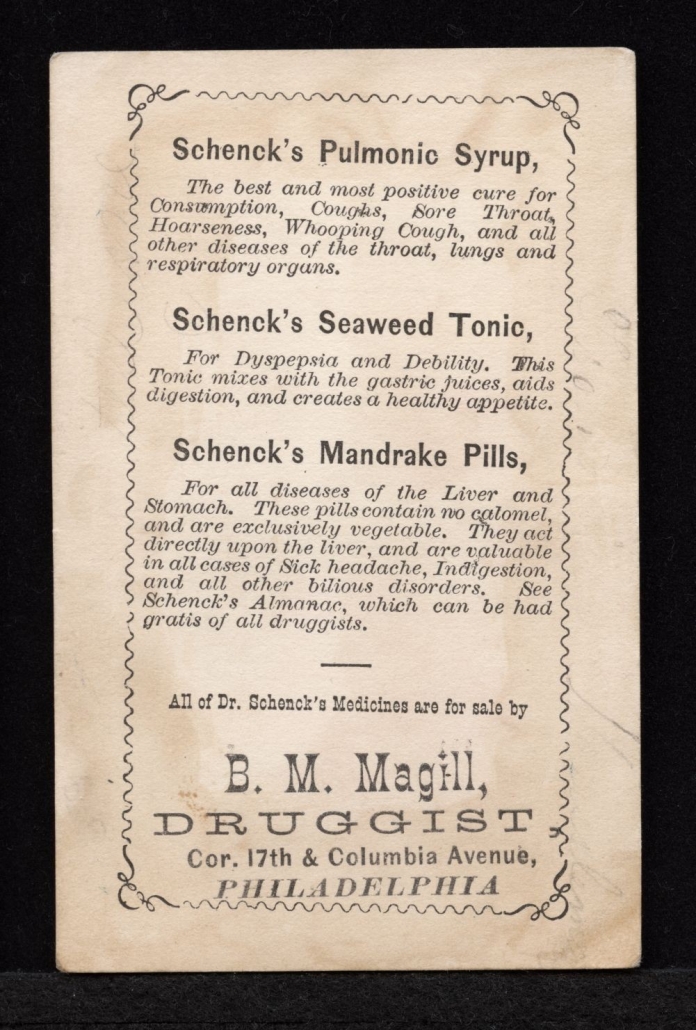

Schenck’s Pulmonic Syrup: A cure-all for consumption, whooping cough, and diseases of the lungs. A medication to be taken in combination with Seaweed Tonic and Mandrake Pills.

Curious, I follow the thread of thought to look up more details. First, I find a vintage color advertisement. Then, I find an archived New York Times article: Schenck’s Pulmonic Syrup The Great Blood Purifier.

Words and phrases jump off the page: hectic fever; Respirometer; purulent. I read and reread the article and reflect on the lost art of poetic medical advertising. I wonder how effective the syrup was. I also wonder whether Dr. Schenck was a respectable medical practitioner or a step above a snake oil salesman. I continue reading the article and learn that Dr. Schenck offered consultations to determine the need for the syrup, prior to use. I’m still undecided.

I’m intrigued and delighted. What an interesting tangent to discover in a seemingly nondescript watercolor.

East Carolina University Digital Collections.

Date: 1870 – 1890|

Identifier: LL02.12.01.45.06

Accessed online: http://digital.lib.ecu.edu/20909

Works Cited

“Schenck’s Pulmonic Syrup the Great Blood Purifier,” The New York Times, April 10, 1865.