North Side of Chestnut St., Extending from Sixth to Seventh St., 1851. – Lauren B. Hewes

Lauren B. Hewes, Vice President for Collections and Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Graphic Arts, American Antiquarian Society

Examined only digital image.

B.R (Benjamin Ridgeway) Evans, 1834-1891.

North Side of Chestnut St., Extending from Sixth to Seventh St., 1851.

Philadelphia, ca. 1880.

Watercolor.

Evans watercolors [P.2298.44]

Gift of Girard Bank and the Friends of the Library Company, 1975.

At first glance, this watercolor depicting a block of busy Chestnut Street in Philadelphia seems to be a faithful depiction of one of the city’s important commercial thoroughfares. Much of the visual information, along with the inscribed title, support the easily-made assumption that the drawing dates from 1851. The buildings are scaled properly for mid-century and the second Chestnut Street Theater, a famous landmark with its carvings of Tragedy and Comedy by William Rush, stands near the corner. In actuality, however, the watercolor was made in the 1880s by artist/architect B. R. Evans.[1] In the 1880s, this section of Chestnut Street was lined with modern gas lamps and telegraph poles, had trolley tracks running down the middle, and the theater (which burned in 1856) had been rebuilt seven blocks away. What gives?

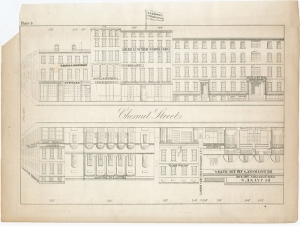

In the 1880s, Evans was commissioned by wealthy city resident and antiquarian Ferdinand J. Dreer (1812-1902) to create a series of scenes of “old” Philadelphia, many based on printed sources and photographs.[2] For this image, Evans likely relied on Rae’s Philadelphia Pictorial Directory & Panoramic Advertiser, published in 1851.[3] The illustrations in Rae’s practical publication are more plan-like than pictorial, carefully delineating shops to allow readers to easily locate specific businesses (fig. 1). Evans reduced the commercial clutter by editing out smaller establishments and modified Rae’s diagram-like design, depicting the street at a more visually pleasing angle. A large expanse of sky allows light to flood down onto the view uninterrupted, and the scene is animated with figures moving up and down clean, wide sidewalks.

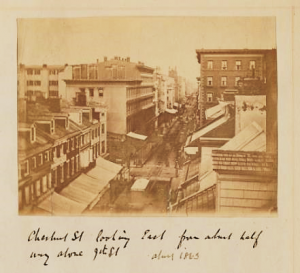

The watercolor is a revisionist view intended to please a patron. Evans left out any evidence of the city’s free black and immigrant populations – the majority of his figures appear to be white and middle class. The usual jumble of posters and sign boards that typically would appear around the theater have been omitted. Photographs from the 1850s and 1860s show a narrower, darker Chestnut Street edged by awnings and covered in advertising signage (fig. 2). While Evans may have used Rae’s directory as a way to see thirty years back in time, his decisions to omit populations and declutter the scene meant that he did not accurately represent 1851 Philadelphia.

None of this likely mattered to the elderly Dreer, who during his lifetime had witnessed the effects of multiple fires in the city and saw the population explode after the Civil War as waves of immigrants from central and southern Europe arrived. When he commissioned the drawings, Dreer was undoubtably aware of the changes caused by repeated cycles of rebuilding and expansion as the city added new transport hubs, trolleys, sewers, gas lights, and telegraph lines, changing forever the Philadelphia of his memory.[4] At times of transformation, some cling to the past, look back and revise what they remember, elevate some aspects while negating or ignoring others. The series of views by Evans, including the north side of Chestnut Street, are evidence of this practice.

Keywords:

Antiquarianism

Chestnut Street

Cityscape

Street scene

Illustrations

Fig. 1 Julio H. Rae, Rae’s Philadelphia Pictorial Directory & Panoramic Advertiser (Philadelphia, 1851), plate 9. Library Company of Philadelphia.

Fig. 2. Album compiled by Joseph Y. Jeanes, Chestnut St. Looking East from about Half Way Above 9th St., ca. 1863. Unprocessed in PR 13 CN 2014:109 [P&P]. Library of Congress.

[1] Evans lists himself as a “practical architect” formerly with Hoxie & Starkwether in the Sunday Dispatch, October 14, 1855, p. 2. His obituary in the Philadelphia Inquirer (July 16, 1891): 6, does not mention an occupation.

[2] Dreer was frequently called an antiquarian in the press, see “Murdoch and the Prentices,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, April 13, 1883, p. 8. Library Company of Philadelphia holds more than 150 of Evans’ designs, which were purchased as a group from the sale of Dreer’s collection in 1913 before coming to LCP in 1975. See Library Company of Philadelphia Annual Report, 1975, p. 6-11. See also Stan V. Henkels at Samuel T. Freeman & Co., Oil Portraits & Engravings. The Collection of the Late Ferdinand J. Dreer, Esq. of Philadelphia. Catalog 1087 (June 6, 1913): lots 170-175.

[3] Julio H. Rae, Rae’s Philadelphia Pictorial Directory & Panoramic Advertiser (Philadelphia, 1851): plates 9 and 10.

[4] Quarter of a Millennium: The Library Company of Philadelphia, 1731-1981 (Philadelphia: The Library Company, 1982): 330. The authors describe the Evans watercolors as depicting structures that were “progress-threatened.” Federal census figures show the city’s population increasing from 121,376 in 1850 to 847,170 by 1880.