[Portrait of an Unidentifed African American woman]

Lauren B. Hewes, Vice President for Collections and Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Graphic Arts, American Antiquarian Society

Examined only digital image.

Attributed to [Broadbent & Co.], Samuel Broadbent, Jr. (1810-1880), photographer.

[Portrait of an Unidentified African American woman].

Philadelphia, ca. 1850s.

Daguerreotype, ¼ plate.

Gift of Mary P. Dunn, [P.9427.13]

At just 4 ¼” x 3 ¼” and highly reflective, this daguerreotype was held in the hands of the viewer and tipped and tilted to reveal the face of the subject. Although the identity of the sitter is unknown, it is part of a collection of portrait photographs associated with the Dickersons, an African American family from Philadelphia. In the 19th century, the Dickerson family supported civic engagement and educational opportunities for the free Black community in the city and championed abolition for the enslaved. The female subject shown here could be a member of the Dickerson family or one of their many friends or associates.[1]

The daguerreotype is attributed to Samuel Broadbent, Jr. who had a studio on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia where he worked with partner Sally G. Hewes (1819-1853), one of the few female photographers in the city. The attribution is based on the set pieces used to frame the sitter – the window sill and the leafy grape vine both appear in other photographs made by Broadbent & Co. between 1851 and 1856.[2]

Most portrait photography in America at this time was entirely transactional. The sitter paid Broadbent for his services and therefore had some say in the resulting image. The use of the window and vine would have been discussed. The subject also likely selected her attire with care; her ruffled cuffs and jewelry depict her as a woman of fashion and means.[3] She touches her neck with one finger and leans forward confidently on the window sill, into the light.

This pose would have been known to Broadbent who, prior to working as a photographer, travelled in New England and the American South painting canvas portraits and ivory miniatures.[4] It also would have been familiar to the sitter and eventual viewers of the daguerreotype who would have seen similar poses used in framing prints or as illustrations in American gift books (figs. 1 & 2). Although much is unknown about this object, by utilizing the visual language of formal portraiture, the daguerreotype reads as a clear and successful likeness.

Keywords

Daguerreotype

Portrait

Illustrations

Fig. 1. Henry Inman, Scraps, detail of upper right corner, lithograph, Philadelphia, 1831. Gift of Charles Henry Taylor. American Antiquarian Society. Detail.

Fig. 2. Joseph Ives Pease after Rembrandt van Rijn, “Peasant Girl,” engraved illustration in American Keepsake: A Christmas and New Year’s Offering (New York: J.C. Riker, 1835), opp. p. 186. American Antiquarian Society.

[1] For more on the Dickerson collection see Library Company of Philadelphia: 1993 Annual Report (Philadelphia: LCP, 1993): 17-24. See also Jasmine Nicole Cobb, Picture Freedom: Remaking Black Visuality in the Early Nineteenth Century (New York: New York University Press, 2005). The Dickersons had three daughters: Mary Anne (b. 1822), Marina (b. 1829), and Amelia (b. c. 1830).

[2] Two similar daguerreotypes recently on the market include Broadbent’s matte stamp. See image of an unknown girl offered by Joan R. Brownstein, Wiscasset, Maine, Stock #2217, and an 1856 daguerreotype of Marnie (sic) Webster sold via Bid Square for Whitley’s Auctioneers, Hollywood, Florida, January 19, 2020, Lot 915.

[3] For more on the use of photography as social agency, see Maurice O. Wallace and Shawn Michelle Smith, eds. Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and African American Identity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012); and Tanya Sheehan, Before Photography, Visualizing Black Freedom. Commonplace, Spring 2016, issue 16.2.5.

[4] American Portrait Miniatures in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010): 198.

Clayton Lewis, Curator of Graphic Materials, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan

Examined only digital image.

Title: [African American woman seated in window frame].

Format: Visual Material

Main Author: [Broadbent, S. (Samuel), 1810-1881]

Published/created: Philadelphia : Samuel S. Broadbent, circa. 1850s

Language: Not applicable

Copy-Specific Note: Leather case with gold edge, oval brass mat.

Copy-Specific Note: [Acquisition info]

Note: Bust length studio portrait of African American woman in a dark dress with tight braided hair, earrings, brooch and ring, seated in window frame with decorative arrangement of ivy

Physical Description: 1 photograph : daguerreotype; plate 105 x 80 mm. (quarter plate format), hand-tinted.

Subjects:

African Americans — portraits — 1850-1860.

Women — 1850-1860.

Daguerreotypes — 1850-1860.

Portrait photographs — 1850-1860.

This is a quarter-plate daguerreotype portrait that appears to be in a standard leather case with an oval brass mat, all of which is typical of American daguerreotypes of the 1850s. The subject is a well-dressed African American woman with tightly braided hair; wearing a simple dark dress with sleeve ruffles on the upper arm; a light-colored V-neck blouse without collar, and jewelry that includes earrings, a brooch, and rings. She is sitting with one arm resting on a window frame, the other arm held below her chin, with one finger resting against her neck. Her expression is one of dignity, composure and perhaps slight fatigue. The composition is framed by a false window with decorative vines along one side.

This daguerreotype by Samuel Broadbent is a terrific example of how the commonplace genre of portrait photography could become a radical statement of inclusion and determination. At the time of violent racist oppression and enslavement in America, an African American woman sat in the gallery of one of Philadelphia’s top portrait photographers. She brought dignity and self-assurance, and comfortably showed possessions indicating material wealth and social status. All of these components can of course be found in the millions of daguerreotype portraits of Caucasian Americans taken in the 19th century. The enormous volume and ubiquity of these images reduces the content to near meaninglessness. For an African American to assert that same place of normalcy in middle-class American society — a place presumed to be occupied by whites — challenged the established norms of the day.

When Samuel Broadbent removed the lens cap from his camera to photographically etch this image on a metal plate, American visual culture was flooded with racist, derogatory, caricatures of African Americans. Frederick Douglass wrote and spoke eloquently about the power of visual culture and his distrust of the ability of white artists to depict Black people. Yet Douglass consented to have his photographic likeness taken again and again, to the extent that he may have literally been the most photographed 19th- century American notable. The overwhelming presence of racist visuals in print culture made clear to many African Americans that the new photographic media —a form that was widely perceived as more truthful and objective — had power when truth was linked to freedom and fiction was justification of enslavement. Photography could be steered towards statements of status, place, and belonging that were backed by the inherent truth of the medium.

Additionally, portrait photograph subjects quickly found that through controlling the expressive details of the pose, they could become active partners in the creation of their own image, in a manner different from the subjugation that often occurred in the hands of a portrait painter. Skilled craftsmen often brought tools of the trade to photo sessions to proudly assert their identity with a career. Details such as jewelry, books and fine clothes signaled rank and status to the viewer. In this way, the subject was a creative partner with some control of the final product.

Who chose the decorative vines that embellish, frame, and soften the context for the sitter in this portrait? Although it was in fact an often-used studio prop of Broadbent’s, the woman who sat within this window frame vignette did so by choice. She is telling us that she too is worthy of the same sentiment and human emotion often denied her race. Yes, this portrait has many generic elements, however this ordinariness is interrupted by the unexpected Blackness of the subject. What was generic and passive for a Caucasian portrait became novel and assertive for that of a Black person, including the gentle blush applied to her cheeks and enhancing her lips — entirely consistent with the flattery applied to images of white counterparts.

The subject of this daguerreotype is unknown to us, nonetheless the image speaks to us with confidence about identity. Through this powerful visual medium she declares “I am somebody. I know who I am. I have a place in this society and I have earned it.”

Keywords:

Clothing and dress

Images of empowerment

Studio photography props and fixtures

Tanya Sheehan, William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Art, Colby College

Examined only digital image.

Broadbent, Samuel, 1810-1880, photographer.

[Portrait of an Unidentified African American woman].

Philadelphia, ca. 1850.

Daguerreotype.

Dickerson family.

Part of the Dickerson Family Collection and the Library’s African American History Graphics Collection.

Cased photos [P.9427.13]

Keywords: studio portrait photography; honorific portraiture; photographic lighting; photographs of African Americans; Frederick Douglass

Description:

The unidentified sitter in this studio portrait is believed to be a member of the Dickerson family, who lived on Locust Street in mid-19th-century Philadelphia. Widowed in 1838, the matriarch of the family managed the bar at the Walnut Street Theatre and raised a family of five; she later married a cabinetmaker and activist in Philadelphia’s growing African American community. The cased portrait was one of seventeen daguerreotypes and tintypes that belonged to the family and entered the Library Company’s collection, along with friendship albums compiled by two of the Dickerson daughters.

Without the sitter’s name, there is much about the portrait we cannot know, from its precise date to the personal circumstances that occasioned its making. Yet seeing the sitter as part of a middle-class African American family like the Dickersons tells us something about the significance and conditions of her photographic experience. As the abolitionist Frederick Douglass proclaimed in the 1860s, the daguerreotype put the act of self-representation into the hands of a great number of Americans. Photographic studios were plentiful in Philadelphia beginning in the 1840s, and the patronizing of such an establishment was considerably less expensive than commissioning a painter to render one’s likeness. For people of African descent, dignifying studio portraits were also powerful expressions of agency that combatted the racist stereotypes dominating popular visual culture. In the daguerreotype under discussion, we see a young woman with a stylish coiffure and dress, adorned by a lace collar and brooch, looking directly at the camera. She gently rests a forearm and elbow on a window frame surrounded by leafy vines. Derived from portrait painting, these distinctive props lent a sense of naturalness to a highly constructed scene; they also help identify the photographer as Samuel Broadbent, who established one of Philadelphia’s finest portrait studios on Chestnut Street in 1851. Broadbent set his sitter’s mouth in what early photographers called a “pleasing expression,” or one in which the lips remain closed and slightly curved upwards. That expression was essential to performances of gentility both within and outside the portrait studio, and so bearing one’s teeth was common only to photographic humor before the turn of the 20th century.

American photographers learned from their trade literature how to dress, pose, and surround their studio patrons so they performed an ideal self for the camera—an ideal defined exclusively in terms of whiteness in the mid-19th century. This meant that people of all races could be posed with the same props and backdrops, but photographers often treated the physical features they associated with nonwhite bodies as technical problems that required careful treatment. Broadbent therefore would have exposed the dark-complexioned members of the Dickerson family to considerable light so their features would be legible and look as “white” as possible in the resulting portraits. Then as now, the light sensitivity of photographic technology was designed to privilege subjects with fair skin tones. Douglass did not dwell on this technical deficiency and the racial hierarchy that motivated it in his celebration of daguerreotypy. For him—and for many historians of photography since—the accessibility of early photographic portraiture and its potential to counter demeaning stereotypes made it a potent social tool for African Americans.

Joy O. Ude, Art teacher, Howry STEAM Academy

Examined only digital image.

Broadbent, Samuel, 1810-1880, photographer.

[Portrait of an Unidentified African American woman].

Philadelphia, ca. 1850.

Daguerreotype.

Dickerson family.

Part of Dickerson Family Collection and the Library’s African American History Graphics Collection.

Cased photos [P.9427.13]

Keywords/Subject headings: Portrait; Daguerreotype; Her gaze.

Description:

Her gaze. As I take in all the detail of this framed daguerreotype, I return to the transfixing gaze of this unnamed woman. Perhaps pensive, but definitely direct. Unwavering. Stately. Is her stare challenging? Is it coy? I can imagine the many stories that could develop from a single look.

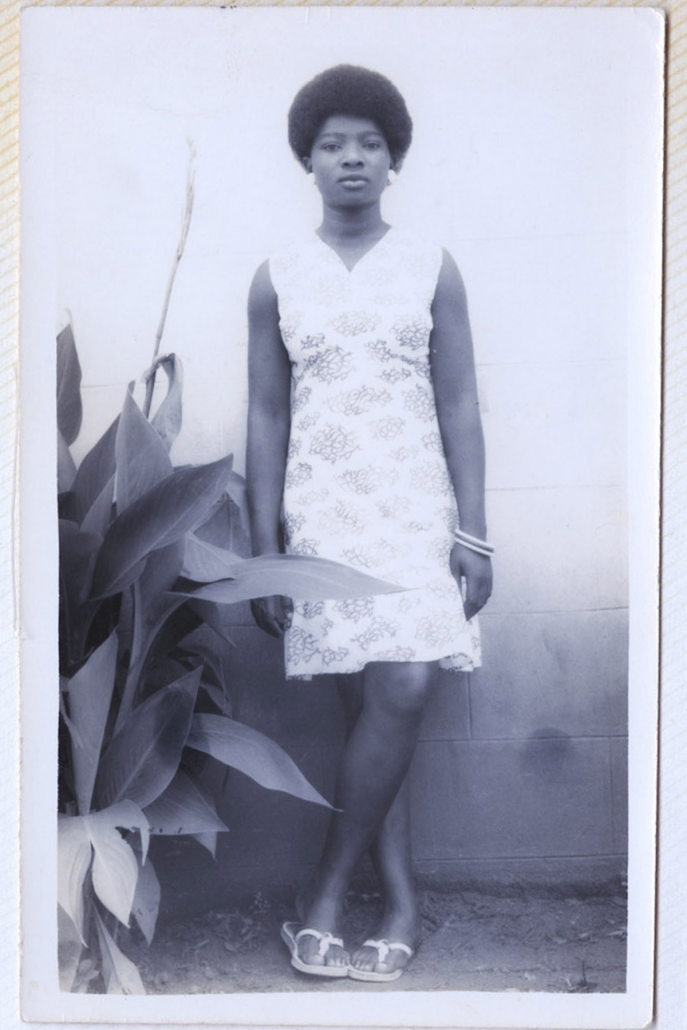

I see in this image a version of the photos my grandmothers, aunts, and mother sat for many times in Nigeria. Striking black and white images, the standard style of West African photo portraits. The daguerreotype precedes the West African portraits, but the effect is the same across decades. In each photo, a confident gaze leveled at the camera. For each woman, a multitude of experiences leading up to a moment captured in time.

There is so much other detail to take in. Her hair, like a crown, framing her face. The ruching and ruffles of her dress and blouse, the collar clasped with a jeweled brooch. The rosy, hand-colored blush in her cheeks added post exposure. The case is well-preserved: a gold-colored mat, framed in various textures of gold, red, and green lines. And yet, I always return to her gaze.

This photo is not of a Black woman portrayed in the typical racist tropes of the time. Not one of the caricatures widely circulated and propagated in advertisements for generations and, in some form, still to this day. Not the mammy, the jezebel, or the sapphire. Instead, I see the portrait of a woman who is poised and proud. A historical photo seldom seen in history books, one that does not focus on emancipated slaves or nursemaids. I see a woman that demands your undivided attention and wills you to see her. How could such dignity go undocumented in text? What is her story?

Mom in Abiriba, c. 1970. Courtesy of Ms. Arit P. Eke-Ude.

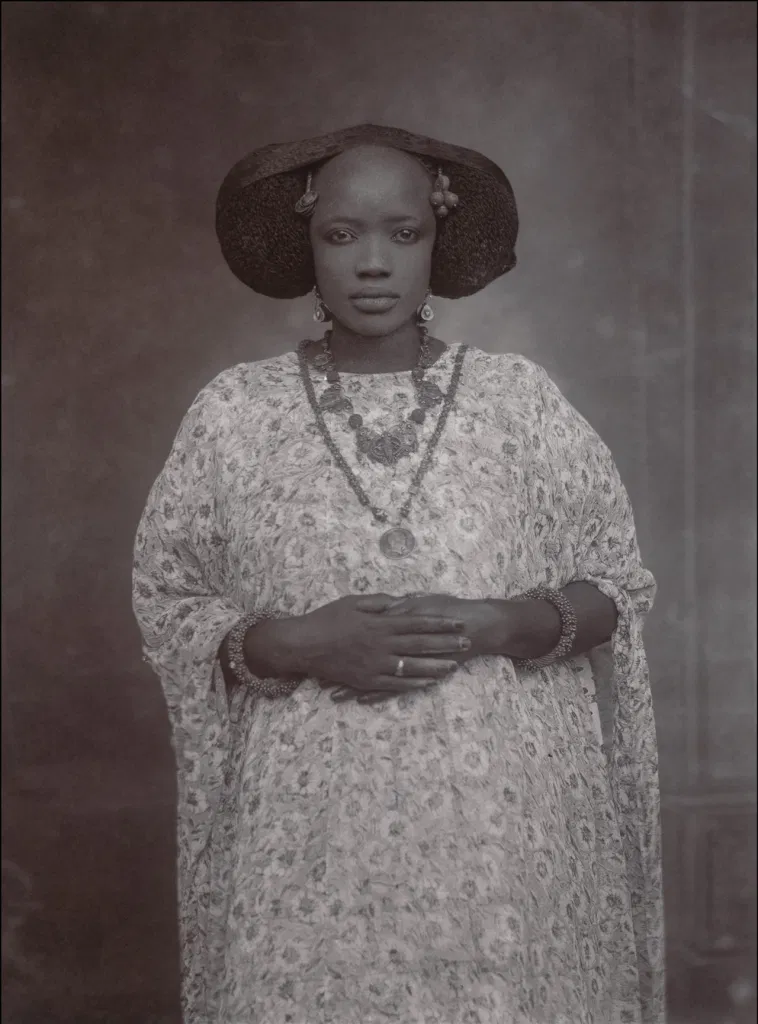

Unknown artist (Senegal)

“Portrait of a Woman” (c. 1910)

Glass negative

6 x 4 in (16.5 x 11.4 cm)

Gift of Susan Mullin Vogel, 2015 (image courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Works Cited

Friedman, Julia. “Illuminating the History of West African Portrait Photography,” December 24, 2015. https://hyperallergic.com/262582/illuminating-the-history-of-west-african-portrait-photography/.