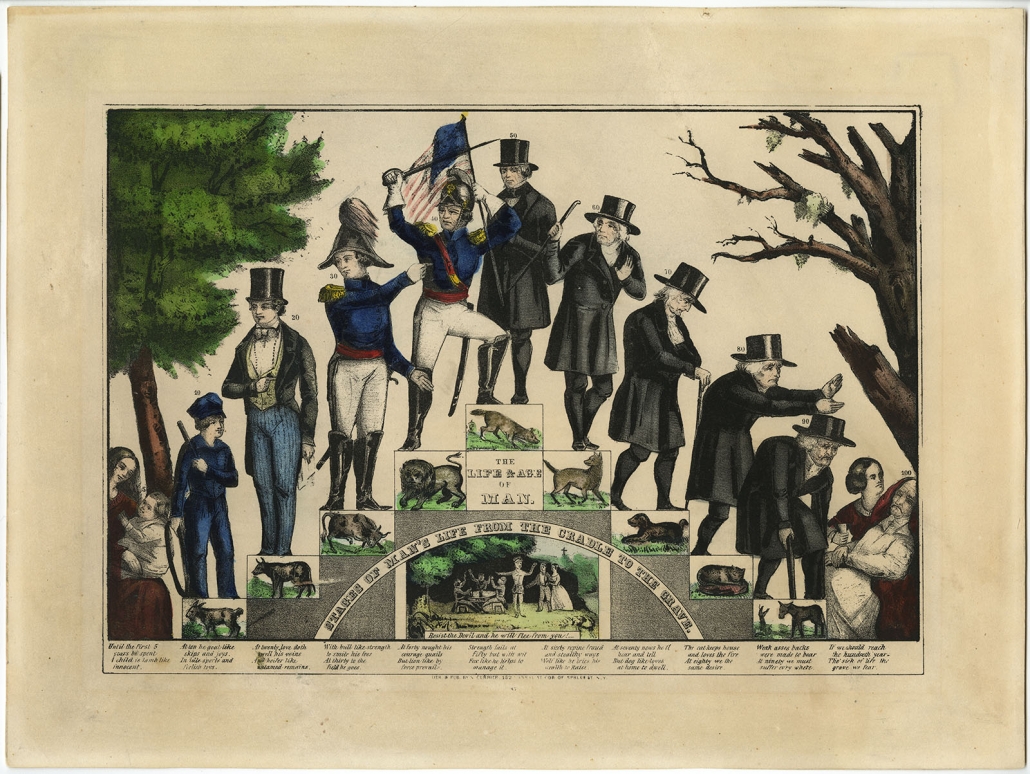

Life & Age of Man. Stages of Man’s Life from the Cradle to the Grave. – Tanya Sheehan

Tanya Sheehan, William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Art, Colby College

Examined only digital image.

Currier, Nathaniel, 1813-1888, artist.

Life & Age of Man. Stages of Man’s Life from the Cradle to the Grave.

New York: N. Currier, [ca. 1847].

Hand-colored lithograph.

*GC – Allegories [P.2004.14.1]

Keywords: Christian values; bourgeois whiteness; patriarchy; masculinity; femininity

Description:

Tracing a single man’s life from boyhood to old age, this popular print maps onto American manhood values associated with white bourgeois Christianity in the antebellum period. Arranged in a pyramidal structure and proceeding from left to right are depictions of the white male protagonist at eleven different stages of his life. The narrative begins with a wide-eyed five-year-old child and ends with a feeble man of one hundred years. Nine stages exist between them, each separated by a decade. Below the man at every stage are four lines of verse that invoke an animal; the beast itself appears above the text, conveying something about his character at a particular age.

Although the print focuses on an ideal man and his maturation, women play an important but limited role within the narrative: that of doting caretaker. A mother cradles her loving child at five years old; a daughter (or nurse) tends to the elderly man as he nears death. These images of womanhood echo artistic depictions of the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ—specifically, the Renaissance tradition of the Madonna and child and that of the pietà, in which Mary supports the body of the dead Christ. Another female presence is suggested in the print, though not seen, in the representation of the man as bourgeois gentleman-suiter at age twenty. Sporting a dapper top hat, waistcoat, and cravat, he stands poised to offer his handkerchief to a young lady, as love “swell[s] his veins.” That the artist chose to compare the man’s twenty-year-old romantic self to an “untamed” heifer, or a young female cow who has not yet had a calf, would surely have struck 19th-century viewers as funny. This clearly feminized masculinity starkly contrasts the images of virile manhood that follow at ages thirty and forty, in which he dons the uniform of an army officer and evokes the strong bull and courageous lion. Women are therefore given considerable power at one moment in the young man’s life, when he is weakened by female charms. The same idea is repeated in a companion print produced by Currier & Ives, Life and Age of Woman: Stages of Woman from the Cradle to the Grave, which describes the female protagonist at age twenty as “a full blown flower.” The “heart of manhood feels her power,” but soon she becomes a subordinate figure who “clings” to her husband, mothers his children, and cares for their home. Feminizing the male protagonist of Life and Age of Man as a heifer may have troubled Victorian audiences, since subsequent versions of the print changed the twenty-year-old man’s animal comparison to an eagle, noted for its strength and dominance as a hunter.

A final female figure appears as part of a finely dressed bourgeois couple within the vignette at the print’s bottom center. Walking arm in arm, the couple encounters a semi-clothed man who beckons them toward a table at which well-dressed men drink and gesture wildly. Quoted from James 4:7, the scene’s caption—“Resist the devil, and he will flee from you”—frames the semi-clothed figure as tempting the goodly couple to a life of sin. Their Christian duty, the Bible instructs, is to submit themselves to God. Familiar with artistic representations of the Garden of Eden, period viewers might have expected to see the woman pictured as the man’s corruptor. But in this encounter with the devil, it is the woman—and the bourgeois domestic life she embodies—who calls the man back from his vices. Note the conspicuous placement of a Christian cross looming over the trees above the wifely figure, and just under the portrayal of the aging man in his most unvirtuous state: like a wolf, at age sixty he resorts to fraud and stealth to increase his wealth. It is through women’s lives of care and virtue, the print argues, that men like the protagonist may find their way into the kingdom of heaven.